|

Between the Lines |

|

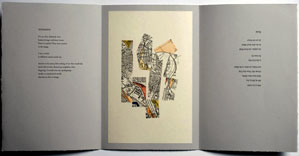

Dan Pagis. Six Poems. Translated by Stephen Mitchell |

|

In creating images to accompany Pagis’ poems, Avadenka dissected many maps. She made visual correlations between train tracks and rivers, mountains and valleys, aligning one with another and making hybrid collages. In By a Thread, she has written that ‘a tumble of letters and chance arrangement of images creates what came before, what we preserve, rescue, retell and make new.’ In these fantastical landscapes routes are truncated in the middle of nowhere, and while the carefully engraved type and earth tones of the hand-coloured lithographs have a nostalgic appeal, the underlying black-and-white grids are reminiscent of aerial photographs of enemy territory. The austere images are printed using polyester plate lithography, a process whereby the image is transferred via a laser printer onto a vellum sheet and then printed directly without the use of chemicals. It’s particularly useful for highly detailed images such as these which would be difficult to reproduce with conventional stone lithography. Avadenka, also an accomplished calligrapher, resisted turning the images into letterforms, but attenuated lines veering into white space can’t help but suggest an alphabet. They remind me of Georges Perec, who wrote in Espèces d’Espaces (Species of Spaces in the excellent translation by John Sturrock): ‘This is how space begins, with words only, traced on the blank page. To describe space, to name it, to trace it, like those portolano-makers who saturated the coastlines with the names of harbours, the names of capes, the names of inlets, until in the end the land was only separated from the sea by a continuous ribbon of text.’ The relationship between language and geographical identity is particularly resonant in the context of Dan Pagis’ work. Pagis was a teenager during the war, and while the Baedeker Raids hit Britain he was imprisoned in a concentration camp in the Ukraine. He escaped, and later moved to Jerusalem where as a scholar and poet he helped shape the modern Hebrew language. Physical location, lost and yet remembered, is a strong theme in his work. Moments of revelation occur in transitional spaces such as the railway carriage or on a tightrope. Even time is permanently on the ‘Point of Departure’, envisaged as a clock speaking: ‘I fly so fast that I’m motionless/and leave behind me/the transparent wake of the past’. Some poems are arrested in mid-sentence, as if in the very process of being erased, and the reader must use their own imagination to fill the absences on the page. ‘For a Literary Survey’, the final poem in this selection, describes a poet who writes with onion juice because ‘it makes excellent invisible ink: … colourless (like the tears the onion causes), and after it dries it doesn’t leave any mark. … Only if it’s brought close to the fire will the writing be revealed, at first hesitantly, a letter here, a letter there, and finally, as it should be, each and every sentence. There’s just one problem. No one knows the secret power of the fire, and who would suspect that the pure page had anything written on it?’ In expressing the persecuted writer’s fear of censorship and the contradictory need for secrecy, Pagis finds an excellent foil in Avadenka. While her handling of typography is subtle to the point of invisibility, her skills as an artist and interpreter ensure that the words assume an unforgettable physical presence on the page. This impressive work demonstrates that history is not only written by historians, it is dreamed by artists and poets. Nancy Campbell is a poet and printmaker who writes regularly on the book arts. |

|

Page created: 02.19.09

Home | About Us | Contact Us | New Arrivals | Fine Press & Artists' Books | Broadsides |Resource Books | Order/Inquiry

Copyright © 2015 Vamp & Tramp, Booksellers, LLC. All rights reserved.